From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

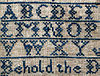

Embroidery is the art or handicraft of decorating fabric or other materials with needle and thread or yarn. Embroidery may also incorporate other materials such as metal strips, pearls, beads, quills, and sequins.

A characteristic of embroidery is that the basic techniques or stitches of the earliest work—chain stitch, buttonhole or blanket stitch, running stitch, satin stitch, cross stitch—remain the fundamental techniques of hand embroidery today.

Machine embroidery, arising in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, mimics hand embroidery, especially in the use of chain stitches, but the "satin stitch" and hemming stitches of machine work rely on the use of multiple threads and resemble hand work in their appearance, not their construction.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Origins

The origins of embroidery are lost in time, but examples survive from ancient Egypt, Iron Age Northern Europe and Zhou Dynasty China. Examples of surviving Chinese chain stitch embroidery worked in silk thread have been dated to the Warring States period (5th-3rd century BC).[1]

The process used to tailor, patch, mend and reinforce cloth fostered the development of sewing techniques, and the decorative possibilities of sewing led to the art of embroidery.[2] In a garment from Migration period Sweden, roughly 300–700 CE, the edges of bands of trimming are reinforced with running stitch, back stitch, stem stitch, tailor's buttonhole stitch, and whipstitching, but it is uncertain whether this work simply reinforces the seams or should be interpreted as decorative embroidery.[3]

The remarkable stability of basic embroidery stitches has been noted:

It is a striking fact that in the development of embroidery ... there are no changes of materials or techniques which can be felt or interpreted as advances from a primitive to a later, more refined stage. On the other hand, we often find in early works a technical accomplishment and high standard of craftsmanship rarely attained in later times. [4]

Elaborately embroidered clothing, religious objects, and household items have been a mark of wealth and status in many cultures including ancient Persia, India, China, Japan, Byzantium, and medieval and Baroque Europe. Traditional folk techniques are passed from generation to generation in cultures as diverse as northern Vietnam, Mexico, and eastern Europe. Professional workshops and guilds arose in medieval England. The output of these workshops, called Opus Anglicanum or "English work," was famous throughout Europe.[5] The manufacture of machine-made embroideries in St. Gallen in eastern Switzerland flourished in the latter half of the 19th century.

[edit] Classification

Embroidery can be classified according to whether the design is stitched on top of or through the foundation fabric, and by the relationship of stitch placement to the fabric.

In free embroidery, designs are applied without regard to the weave of the underlying fabric. Examples include crewel and traditional Chinese and Japanese embroidery.

Counted-thread embroidery patterns are created by making stitches over a predetermined number of threads in the foundation fabric. Counted-thread embroidery is more easily worked on an even-weave foundation fabric such as embroidery canvas, aida cloth, or specially woven cotton and linen fabrics although non-evenweave linen is used as well. Examples include needlepoint and some forms of blackwork embroidery.

In canvas work threads are stitched through a fabric mesh to create a dense pattern that completely covers the foundation fabric. Traditional canvas work such as bargello is a counted-thread technique.[6] Since the 19th century, printed and hand painted canvases where the painted or printed image serves as color-guide have eliminated the need for counting threads. These are particularly suited to pictorial rather than geometric designs deriving from the Berlin wool work craze of the early 19th century.[7][8][9]

In drawn thread work and cutwork, the foundation fabric is deformed or cut away to create holes that are then embellished with embroidery, often with thread in the same color as the foundation fabric. These techniques are the progenitors of needlelace. When created in white thread on white linen or cotton, this work is collectively referred to as whitework.[10]

[edit] Materials

The fabrics and yarns used in traditional embroidery vary from place to place. Wool, linen, and silk have been in use for thousands of years for both fabric and yarn. Today, embroidery thread is manufactured in cotton, rayon, and novelty yarns as well as in traditional wool, linen, and silk. Ribbon embroidery uses narrow ribbon in silk or silk/organza blend ribbon, most commonly to create floral motifs.[11]

Surface embroidery techniques such as chain stitch and couching or laid-work are the most economical of expensive yarns; couching is generally used for goldwork. Canvas work techniques, in which large amounts of yarn are buried on the back of the work, use more materials but provide a sturdier and more substantial finished textile.[9]

In both canvas work and surface embroidery an embroidery hoop or frame can be used to stretch the material and ensure even stitching tension that prevents pattern distortion. Modern canvas work tends to follow very symmetrical counted stitching patterns with designs developing from repetition of one or only a few similar stitches in a variety of thread hues. Many forms of surface embroidery, by contrast, are distinguished by a wide range of different stitching patterns used in a single piece of work.[12]

[edit] Machine

Much contemporary embroidery is stitched with a computerized embroidery machine using patterns "digitized" with embroidery software. In machine embroidery, different types of "fills" add texture and design to the finished work. Machine embroidery is used to add logos and monograms to business shirts or jackets, gifts, and team apparel as well as to decorate household linens, draperies, and decorator fabrics that mimic the elaborate hand embroidery of the past.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Gillow and Bryan 1999, p. 178

- ^ Gillow and Bryan 1999, p. 12

- ^ Coatsworth, Elizabeth: "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", in Netherton and Owen-Crocker 2005, p. 2

- ^ Marie Schuette and Sigrid Muller-Christensen, The Art of Embroidery translated by Donald King, Thames and Hudson, 1964, quoted in Netherton and Owen-Crocker 2005, p. 2

- ^ Levey and King 1993, p. 12

- ^ Gillow and Bryan 1999, p. 198

- ^ Embroiderers' Guild 1984, p. 54

- ^ Berman 2000

- ^ a b Readers Digest 1979, p. 112-115

- ^ Readers Digest 1979, pp. 74-91

- ^ van Niekerk 2006

- ^ Readers Digest 1979, pp. 1-19, 112-117

[edit] References

- Berman, Pat (2000). "Berlin Work". American Needlepoint Guild. http://www.needlepoint.org/Archives/01-01/berlinwork.php. Retrieved on 2009-01-24.

- Caulfield, S.F.A., and B.C. Saward (1885). The Dictionary of Needlework.

- Embroiderers' Guild Practical Study Group (1984). Needlework School. QED Publishers. ISBN 0890097852.

- Gillow, John, and Bryan Sentance (1999). World Textiles. Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-2621-5.

- Lemon, Jane (2004). Metal Thread Embroidery. Sterling. ISBN 071348926X.

- Levey, S. M. and D. King (1993). The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection Vol. 3: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750. Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN ISBN 1851771263.

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, (2005). Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1. Boydell Press. ISBN 1843831236.

- Readers Digest (1979). Complete Guide to Needlework. Readers Digest. ISBN ISBN 0-89577-059-8.

- van Niekerk, Di (2006). A Perfect World in Ribbon Embroidery and Stumpwork. ISBN ISBN 1-84448-231-6.

- Wilson, David M. (1985). The Bayeux Tapestry. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500251223.

[edit] External links

- Embroidery at the Open Directory Project

|

No comments:

Post a Comment